PUBLISHERS NOTE: This was the first story we published when we launched the blog last decade. Seems like yesterday.

By Vic Garbarini

“If you weren’t around when Beatlemania hit, you missed something truly phenomenal. They had as much impact on people as World War II, but in a positive way.” – Ozzy Osbourne

When I first asked Paul McCartney in 1980 how and why he felt his little four-man band from Liverpool had transformed our culture, he gave a perfectly coherent answer involving Hamburg, the Ed Sullivan Show, their dedication to their craft and luck. It all made sense, and yet it came nowhere near explaining the multidimensional creative energy that seemed to be released into or rather through our bodies, hearts, minds and souls by their music. How do you describe going through spiritual puberty? Of being a 12-year-old kid watching four guys on the Ed Sullivan Show fuse your molecules into an ecstatic realization that nothing would ever be the same again. (And 48 years later to understand, perhaps a bit more comprehensively, that that taste of a higher freedom was grounded in a higher reality than mere Freudian sexual dysfunction or mass hysteria (though there are traces of all that around the edges of the event).

“It felt like we were all in the Beatles at that point in the 60s. We were living in and through their music and this expanded consciousness it had opened us to - which may sound odd today, but it was like that.” –Andy Summers, The Police

“I Am He as You Are We and We Are All Together.” - “I Am The Walrus” – John Lennon

Which doesn’t mean you missed out on the whole party if you came of age in the 70s or later. Led Zeppelin, Nirvana or the White Stripes may have been your personal supernova; all further manifestations of original Big Bang that birthed the Beatles. Needless to say, we’re not talking about four transcendent sages. This energetic revelation/revolution manifested through four young men whose egos and ignorance could often cause them to lose the plot, though rarely the music (see Ringo’s remarks at the end of the piece).

It would take me almost 25 years to interview all the surviving Beatles, plus Sir George Martin and their brilliant engineer Geoff Emerick. I did consult on John Lennon and Yoko’s first interview after their five-year silence for Newsweek magazine, and John did answer a few of my questions, But his assassination in December of 1980 meant I would never meet him in person.

I should thank legendary publicist Bob Merlis for literally handing George Harrison the phone in 1992, and saying, “I think you should talk to Vic.” And kudos to Guitar World Editor Brad Tolinski for going out of his way to set up an additional interview for me with Sir George Martin – although he had already had an excellent Martin interview from another writer (he ran both). And extra special thanks to EMI’s Jennifer Ballantyne, who the Beatles are very fortunate to have representing them at EMI–US, and for whose grace and hard work I am truly grateful.

But getting back to McCartney: More recently Rolling Stone’s Anthony De Curtis asked Paul the same question about what the hell the caused the whole Beatles thing. This time Paul essentially answered with one word: Magic.

Magic. Now we’re getting somewhere. The word “magic” does not imply irrationality or illusion, not in its usage here, “magic” is that which we have neither the consciousness, understanding or vocabulary to squeeze into our limited world view, at least for now. If you lived in 1776 and heard a radio broadcast, that would seem like unfathomable magic. Same would hold true for a microwave oven, an airplane or even Cinnabons. Especially Cinnabons.

But of course there were many people in the world, mostly in what we condescendingly refer to as the Third World, who understand how to recognize, interpret and work with “the Magic” for centuries. While we in the West were learning to build bridges to link our outer world, they were creating structures to connect, illuminate and transform our inner lives. One cool September evening in Istanbul, a few months after I first interviewed McCartney, a friend and I

Were invited to attend a private music recital by an extraordinary group of Sufi musicians in an ancient tekkeon the Asian side of the Bosporus (think of Sufis as the Zen Masters, or Tibetan monks of the Middle East). For a few hours their transcendent, radiant music once again fused my molecules into that state of blissful consciousness, I asked in my village idiot Turkish if they found anything of comparable value in Western music. “Certainly,” the ney player replied. “We listen to the Beatles, to Dylan, to Ornette Coleman.” Noticing my slightly stunned expression, he laughed, then continued, “These are the people who are helping to bring the higher healing, transformative energies in music into your society. We don’t understand most of the words, but we can feel and sense the power and qualities of that music nonetheless. Can’t you?”

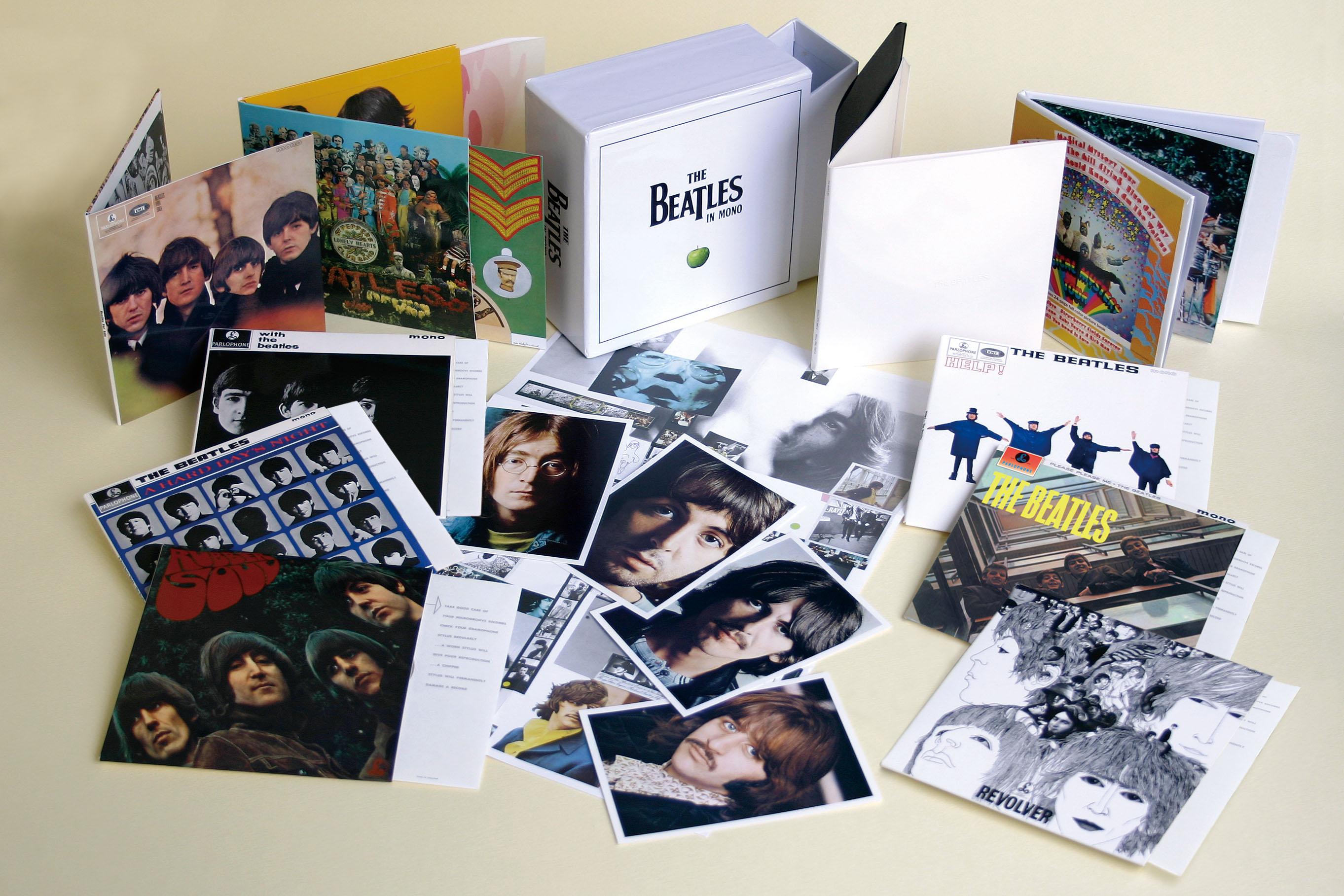

“It was twenty years ago today (okay, more like 23, actually), since the Beatles catalogue was first issued on CD in 1987. If you’d been raised on the original American vinyl Fab Four catalogue you were in for a bit of a shock. EMI then, as now, released the CDs in their original UK configurations, which often featured different cuts from the US releases—at least until Sgt Pepper’s. One key reason for this was the Beatles and Sir George Martin in particular’s penchant for leaving songs released as singles off their albums. (See his explanation in the “Court-Martial of Sgt Pepper’s" segment.)

The good news is that the team of engineers at Abbey Road spent four years painstakingly remastering every inch of tape, resulting in a brilliantly repolished set of 14 stereo titles over 16 albums. Plus there’s a limited edition set of Mono Masters totaling 12 discs, which, unlike the stereo discs, you can’t legally buy individually. Remember, the albums have been remastered, not remixed. The CDs are clearer and more dynamic sounding because the tracks comprising each song have been buffed and cleaned – remixing would mean changing the balance, say between the level of a vocal, guitar or any instrument in relation to other sounds in a song – and that has not been done here.

According to the audio restoration engineers involved, “It was agreed that electrical clicks, microphone vocal pops, excessive sibilance and bad edits should be improved where possible, so long as it didn’t impact on the original integrity of the songs.” Meaning little goofs have been repaired, but you probably won’t be aware of them consciously, though they do smooth out the listening experience. They’ve opted for the safe route, carefully wiping the dust and grime off the Sistine Chapel, but not attempting to touch up the paint.

So after a 23 year wait, you’re getting the respectable sonic upgrade you would expect, but not a dramatically improved, mind-altering display of sonic alchemy. If you’re looking for the latter, head straight for the soundtrack to Love, the astonishing musical mash-up masterminded by Sir George Martin and his son Giles for the Beatles themed Cirque D’Soleil show a few years ago. Pere et fils, Martin daringly ranged over the entire Beatles oeuvre, taking pieces of aural DNA from individual songs and re-assembling them to create something entirely new, yet familiar. A guitar or drum break from Abbey Road would be dropped into a fragment of a song from Pepper, which would blend into something from Rubber Soul. It could have been a mess, instead it is a seamless, thrilling work of genius – imagine the concept of the medley on the second side of Abbey Roadapplied to the entire Beatles catalogue, with heightened dynamics. Every Beatles fan should experience it.

If you want to hear Beatles tracks in their original forms that have been remixed, try and dig up a copy of 1999’s expanded Yellow Submarine Soundtrack. At the time, George Harrison confirmed that many of the tracks, which now included every Beatle song that appeared in the movie, were indeed re-mixed. In particular, check out Harrison’s own “It’s All Too Much” a little known Sgt Pepper’s era outtake that was tarted up forYellow Submarine. The Remasters version still sounds thin and flat, whereas the re-mixed Yellow Submarineversion pulverizes you with McCartney’s mega –Hendrixian guitar intro, Harrison’s steaming organ riffs and Ringo’s pounding drums – All previously buried in the original compressed mix, which was limited by primitive 60s technology.

John Lennon once said, “You haven’t heard Sgt. Pepper’sunless you’ve heard it in mono.” Then again, most of the records John listened to back in the day, including his own, were in mono. It helps to know that the Beatles and Martin basically mixed almost all the albums in mono – stereo hadn’t really caught on until the mid-to-late 60s – the band often didn’t even bother to stick around for the stereo mixes. A few of the relatively rushed stereo tracks on the earlier albums can really sound quite bizarre, but usually only if you’re listening on headphones, where just a tambourine and a few backing vocals in one ear, and the rest of the song in the other, can sound pretty strange at times.

So stereo remasters or mono: which is better? Honestly, it’s a matter of personal taste. Although collectors are scooping up the limited mono sets, most people of course opt for stereo. Abbey Road and The Bealtes aka the White Album, are the top selling individual discs while the entire Beatles catalogue has just been certified as the top selling CD collection of the decade. That’s impressive when you realize that they’ve barely been on sale over 3 months (release date was 9/09/09). But not so surprising when you factor in that fans, which include everybody from the youngest rappers and indie bands to Vladimir Putin, have been waiting nearly a quarter of a century for a quality reissue of the greatest catalogue in rock history.

Finally, depending on who you talk to, CD sales have fallen precipitously this decade by anywhere from 50% - 70%. And you still can’t buy the Beatles individual CDs and songs as individual downloads.

So may I introduce to you, the act you’ve known for all these years…

Hamburg vs Liverpool.

VG: John Lennon once said, “I grew up in Hamburg, not Liverpool.” Was that also true of the Beatles as a group?

George: Oh, yeah. Before Hamburg we didn’t have a clue. We’d never really done any professional gigs. We’d never had a drummer longer than one night at a time. So we were very ropey, just young kids. I was the youngest, only 17, and you had to be 18 to play in the German clubs – plus we had no visas. When we first arrived in Hamburg, we weren’t a unit as a band yet. Suddenly we were playing eight hours a day – like a full workday. We did that day and night for a total of 11 or 12 months, on and off over a two year period. It was pretty intense.

Paul: When we started off in Hamburg, we had no audience, so we had to work our asses off to get people in. People would appear at the door of the club while we were on stage, and there’d be nobody at the tables. We used to get them in to sell beer. The minute we saw someone we’d kick into (leaps out of chair, sings) “Dancing in the streets tonight...” and justrock out, and we’d got three of them in! We were working eight hours a day – a full factory day. Other bands in Liverpool didn’t do that. We eventually sold those Hamburg clubs out, which is when we realized it was going to get really big. Then we went back to the Cavern in Liverpool – same thing happened there. There was this incredible excitement, We knew something we were doing must have been right.

George: At first we’d play all our heroes’ music: Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, The Everly Brothers, Fats Domino, Ray Charles and Carl Perkins. Eventually, we had to stretch and play a lot of new stuff. If you’re coming in with a hangover from the night before, and it’s 3pm and the club is pretty empty, you’re not going to jump up and down and start singing "What’d I Say?" You’re going to sit down and play standards like "Moonglow" and "A Taste Of Honey". That’s also where we developed our harmonies, from doing girl-group stuff like the Shirelles. Eventually, all those elements fused together.

The Beatles were also spurred on in Hamburg by another Liverpool group playing just down the street: Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, featuring the vocals and drumming of one Richard “Ringo” Starkey. He remembers checking out his rivals.

Ringo: Hamburg is really where we got our stuff together. If we hadn’t have gone there I don’t know how, or even if, I would have continued playing. Between us, our two groups played at least 12 hours a day. It forced us to stretch and learn to play anything we could think of. At the time, the Beatles impressed me more as vocalists than musicians. Paul wasn’t actually playing an instrument, he was strumming on a two-string guitar just so he could hold something. They could rock as a band, but my main memory is of Paul singing his balls off with that two-string guitar. The Beatles and Rory both really wanted to be the top band – we’d do any craziness to get the audience going. The competition, and all those hours on stage, really forced us to learn our craft. It was like taking a cram course.

A Hard Year’s Tour (1964-1965).

Through the Hard Day’s Night and Help! era the Beatles toured incessantly, driving their audiences around the world into states of Dionysian frenzy. Yet they soon became stuck in a musician’s nightmare – trapped in a bubble of screeching white noise. And worse.

Ringo: The main problem with being on tour was that no matter how well or badly we played, we got the same reaction. It didn’t matter if we’d done the worst show ever, they scream and applaud anyway. As a musician that doesn’t help you – it screws with your head. At that point the audience didn’t come to our shows to hear music – they came to watch four guys mime. It must have looked like miming, because nobody could hear anything at all, including us. I used to lean over and try and read Paul’s lips to keep track of where we were at. I couldn’t do anything except keep a straight beat or we’d lose track of the song. If I did go off into a fill, you could feel everybody get nervous and glance around, wondering ‘Where the hell are we?’ After a while we figured we could just go out there and fartand still get the same manic response. It wasn’t appreciation for the act anymore, it was just a reaction to the phenomenon.

George: It was ridiculous: we were out in the center of some stadium with our 30 watt amps – the kind people use today in their bedrooms or to play a small club. And nothing was even mic’ed up through the PA systems. They just had to listen to our little amps and two vocal mics – until we got those really big 100 watt amps for the Shea Stadium show. [Laughs] It was so surreal, sometimes we’d just play rubbish. At Shea, John was playing that little Vox organ with his elbow. We were just laughing hysterically instead of singing the backup vocals. I really couldn’t hear a thing. Today, if you can get a good balance on your monitors, it’s so much easier to hear your vocals and stay in pitch. When you can’t hear your vocals on stage, you tend to go over the top and sing sharp – which we often did back then.

Paul: I remember many times just sitting outside concert halls waiting for the police to escort us in and thinking, "Jesus Christ, I really don’t want to go through with this. We’ve done enough, let’s take the money and run. Let’s go down to Brighton or something!" If we could have gotten away with it, we would have.

Ringo: The worst experience touring for me was Montreal, where they threatened to shoot me. They said they were going to get the "little English Jew". So they had a plainclothes detective onstage with me that night. He was ready to catch the bullets, I guess. At the end of every number I’d come down hard on the cymbals, and then grab them at the bottom and tilt them up like two shields to protect me. In Quebec they were against the Queen and all, so that explains the English part. But the weird thing is, I’m not even Jewish!

Rubber Soul/Revolver = Revolution.

George: Around the time of Rubber Soul and Revolver I became more...conscious, I guess is the word. Everything we were doing became deeper and more meaningful. Without getting into the drug question...but I have to get into it, really. I was young and naive, and all the music really started happening for me when we started smoking reefers. You listen deeper, somehow. But I don’t really want to be responsible for other people smoking dope because I’ve come out the other end of that now and I don’t do it anymore. There are better and [less dangerous] ways of reaching much deeper places in yourself, as I discovered through Indian music and spirituality. You learn to get your own cosmic lightning conductor and nature supports you. You begin to realize that you are very small, and yet everyone and every grain of sand is very important.

Paul: "You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away" and "Norwegian Wood" and those kind of tunes were just John doing Dylan. He’d just come out and we were big fans of his. So that acoustic feel onRubber Soul, and even earlier, were just what we were experimenting with at the time.

George: As for Rubber Soul and the Beatles and Dylan inspiring each other – Dylan once wrote a song called "Fourth Time Around". To my mind it was always about how John and Paul, from listening to Bob’s early stuff, wrote songs like "Norwegian Wood". Bob sounded like he’d listened to that, and wrote the same basic song again, calling it "Fourth Time Around" – as if the same song kept bouncing back and forth between us.

Paul: We were in Germany just before Rubber Soul came out. I started listening to the album one night and I got really down because I thought the whole thing was out of tune…No, wait, that was Revolver. Anyway, everybody had to reassure me that it was okay.

George: I was playing guitar with Bob (Dylan) at his house and I remember saying, “How do you write all those amazing words?” And he shrugged, and said, “Well, how about all those chords you come up with?” So I started playing and said it was just all these funny chords people showed me when I was a kid. Then I played two lush Major7th in a row to demonstrate, and suddenly thought, “Ah, this sounds like a tune here.” Bob started singing a melody and some lyrics, and it eventually became "I’d Have You Anytime", which became the opening song on my solo album All Things Must Pass.

Sir George Martin: For me, "In My Life" has got to be right up there with "Strawberry Fields" as my favorite Beatles tracks, for a number of reasons. Lyrically, the words have grown to mean so much to me. I’ve had the good fortune to work with so many people, some of who are gone, as the words say, including John. A lot of younger artists are realizing that John had a very tender, soft side.

There was this strange myth that grew up that he was the Teddy Boy, the rocker, and Paul was the softy. But Paul did songs like "Helter Skelter" and John did "In My Life", "Julia", "Across the Universe", and all those songs on Imagine. The vocal on "In My Life" is one of John’s most exquisite – it couldn’t have been done by anyone else. He hated his voice and always wanted me to distort it or change it. He had a truly wonderful voice, but don’t we all look in the mirror and say, “God, I think my nose is awful” – and no one else knows what we’re on about? It’s human nature, isn’t it?

VG: The famous "harpsichord" solo that was actually a sped-up piano – why not use the real thing?

Martin: Because John actually had no idea of what I was going to do, and I didn’t know if he’d like the result. I did it very quickly one night while the boys were having dinner and I used a grand piano because that’s what was available. I knew that by doubling up the speed on tape it would cut the decay of each note in half so it sounded very clipped like a harpsichord, which I intended all along. I played it for him when he came back from dinner. Happily, he said, “That’s great, we’ll keep it.”

VG: Paul claimed a few years ago that he clearly remembers writing the music for "In My Life". What’s your memory of who did what?

Martin: John presented the song to me, so I always presumed the music was his. Back when he was writing it, maybe Paul was with him and gave him a tune [pauses]. And in retrospect, it certainly sounds more like Paul’s music rather than John’s. But John claimed it was his song, so I have to accept that.

Sgt. Pepper: The Flawed Masterpiece.

Paul: I had this idea that it was going to be an album by another band that wasn’t us. We’d just imagine all the time that it wasn’t us playing, it was Pepper’s band. It was a nice little device to give us some distance from the whole Beatles identity. It changed a lot in the process but that was the basic idea behind it.

However, George was preoccupied and Ringo was… bored.

Ringo: There were just so many overdubs on Pepper. The backing tracks were fine, but there was so much to be put on top of them you couldn’t tell how good the songs really were ‘til we finished six months later. With all those orchestras and whatnot we were virtually reduced to being a session group on our own album.

George: When I got back from this incredible journey to India, we were about to do Sgt. Pepper’s, which I don’t remember much at all. I was in my own little world and my ears were filled with ragas and sarangis. So I really wasn’t into sitting there and thrashing through [sings nasally] “I’m Fixing A Hole…” But if you listen to "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds", you’ll hear me try to play the melody on guitar with John’s voice, which is what the instrumentalist does in Hindustani vocal music.

See The Court-Martial of Sgt. Pepper to learn what the album might have been.

The White Stuff.

Paul: The White Album, that was thetension album. We were all in the midst of the psychedelic thing, or just coming out of it. We were about to break up, and that was tense and weird in itself. Never before had we recorded with beds in the studio [ie, Yoko] and people visiting for hours on end: business meetings and all that. There was a lot of friction. Musical differences played a part, too. I remember telling George not to play guitar on "Hey Jude". He wanted to echo riffs after the vocal phrases, which I didn’t think was appropriate. He didn’t see it like that and it was a bit of a number for me to have to dare to tell George Harrison – who’s one of the greats, I think – not to play guitar on a track. It was like an insult. But that’s how we wound up doing a lot of our stuff.

Ringo: It was so tense I actually quit the group for a while, which is why Paul wound up playing drums on "Back In The USSR". Looking back we were going through a kind of madness: Everyone thought the other three were friends and it turned out none of us were getting along with each other. We were all just paranoid and crazy. Yet in the end, I always felt the White Album was better than Pepper’s because we were back to playing as a real band again together, not sitting around waiting for all those overdubs to be finished.

VG: Paul gets blamed for trying to "take over" the Beatles after Brian Epstein died. George said he was a control freak, Ringo walked out of the White Album sessions, and John’s resentment – and heroin use – was not exactly a secret. Meanwhile, Paul felt that the band was falling apart, and if he hadn’t pushed them, it would have been all over. How did it seem to you?

Martin: All those things were true. Paul was pushy and George hated it. Paul is always pushy, anyway. He was like that even before then. And Paul’s equally right in that if he hadn’t been pushy, they would’ve fallen apart.

Paul: No matter who puts on the great show out front, basically, we’re all these very frail...imitators. We used to nick songs, titles, John and I. "Helter Skelter" came about because I read in the Melody Maker that The Who had made the "loudest, most raucous rock and roll record." I didn’t know what song they were talking about [I Can See For Miles– Ed.] but it made me think, "Right, we’ve got to do that!" We were the greatest criminals going.

Ringo: Paul wasn’t a musical director. Paul just likes to work – he’s a workaholic. We’d all be wandering around the garden on a summer’s day and there’d come this phone call. It would be Paul saying, "I think it’s time we went back to work lads." So he would call us together, but not as musical director, because if, for instance, George wrote a particular track, then he’d be director on that, and so on. Though in the end, you could say that George was in the most difficult position, because John and Paul even wanted to write his solos and George was very frustrated. So there was some friction, but it all got cleared up in the end.

George: Well...sometimes Paul "dictated for the better of a song" but at the same time he also pre-empted some good stuff that could have gone in a different direction. George Martin did that too. But they’ve all apologized to me for all that over the years.

VG: But you were upset enough about all this to leave the band for a short time during the Let It Be sessions. Reportedly, these problems were brewing for a while. What was it that disturbed you about what Paul and John were doing?

George: At that point in time, Paul couldn’t see beyond himself. He was really on a roll – but it was a roll encompassing only his own self. And in his mind, everything that was going on around him was just there to accompany him. He wasn’t sensitive to stepping on other people’s egos or feelings. Having said that, when it came to do the occasional song of mine – although it was usually difficult to get to that point – Paul would always be really creative with what he’d contribute. For instance, that galloping piano part on "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" was Paul’s and it’s absolutely brilliant. On my solo tours I’d get our keyboardist to play it note for note. And you just have to listen to the bass line on "Something" to know that, when he wanted to, Paul could give a lot.

VG: How difficult was it to squeeze your songs in between the two most famous songwriters in rock?

George: To get it straight, if it hadn’t been for John and Paul, I probably wouldn’t have thought about writing a song – at least not until much later. But it’s true, it wasn’t easy in those days getting up enthusiasm for any of my songs. We’d be in a recording situation, churning through all this Lennon/McCartney, Lennon/McCartney, Lennon/McCartney! Then I’d ask [meekly] “Can we do one of these?” When we started recording "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" it was just me playing the acoustic guitar and singing it. [Note: This exquisite, ethereal version appears on theAnthology 3 CD – Ed.] and nobody was interested. Well, Ringo probably was, but John and Paul weren’t. When I went home that night I was really disappointed. I thought, “This is really quite a good song, it’s not as if it’s shitty!” The next day, I happened to drive back into London with Eric Clapton, and while we were in the car I suddenly said, “Why don’t you come and play on this track?” And he said, “Oh, I couldn’t do that. The others wouldn’t like it.”

VG: Was that a clearly verboten thing with the Beatles – having another major artist play on an album?

George: Well, it wasn’t so much verboten - it’s just that none of us had ever done it before. So Eric was reluctant, and I finally said, "Well sod them! It’s my song and I’d really like you to come down to the studio!" Which he did. And suddenly everybody starting paying attention and not fooling around so much. They same thing happened during the Let It Be/Get Back movie and sessions, when everyone was fighting. Billy Preston came into our office and I pulled him into the studio and got him playing electric piano, and the band suddenly stopped messing around and started working together again.

VG: The medley on side two of Abbey Road is a seamless masterpiece. It would probably take a modern band ages to put together, even with digital technology. How did you manage to manage all that with primitive four- and eight-track recorders?

George: We worked it all out carefully in advance. All those mini-songs were partly completed tunes, some were written while we were in India the year before. So there was just a bit of chorus here and verse there. So we welded them all together into a routine. Then we actually learned to play the whole thing live. Obviously, there were overdubs. Later when we added the vocals, we basically did the same thing. From the best of my memory, we learned all the backing tracks, and as each piece came up on tape, like "Golden Slumbers", we’d all jump in with the vocal harmonies. Because when you're working with only a few tracks, you’ve got to get as much as possible on each one.

Ringo: I really enjoyed doing the Abbey Road medley, where we had all those bits about Polyethylene Pams coming through bathroom windows and the rest, strung together with tom-toms and other madness. All those parts were done separately at first. When we finished one segment, we’d play along with the completed tape of that bit to synchronize our timing and then we’d come into the next section. Though some of them were complete edits.

Martin: Shall I tell you the secret to that? First, we recorded the various song fragments separately – but with preambles and run-ons so that they would overlap when we put them together – but the different tempo changes were created by cross-fading and cutting. Meaning the songs came out that way because I cut them right on a beat. It was a little quirky, but it sounded good. For example, in the "You Never Give Me Your Money" section, the tempo changes radically round about the “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, all good children go to heaven" bit. And that is because of a cut, meaning an edit. You can clearly hear it change from a 12/8 beat to a 5/8, and then go into a fast four starting at that point.

VG: So the music in the medley wasn’t originally written with those tempos – you put them in while editing?

Martin: In the sense that they shifted and ended up that way because I cut them – edited them – that way, yes. In those days you were literally cutting the recording tape with a razor blade. I remember cutting a bar out of "She’s Leaving Home" because I didn’t like the cello part. If you listen for it, you’ll hear I had it come in a little early. That made it sound a little bit unusual, but it added a little piquancy to it.

And In The End...

VG: Just one more question. With all the personal conflict from theWhite Album through Let It Be, how did you guys continue to create such great music?

Ringo: Because no matter what was going down, we all still loved to play. Once we were sitting there as four musicians it all came together again. It was like mental telepathy when we’d play – you knew when someone else was going to do something. We’d all do things together without anyone saying anything. Things would happen like…magic. It was magical all the time.

The Beatles reissues are out now on EMI

Saturday, February 13, 2010 at 12:21AM

Saturday, February 13, 2010 at 12:21AM

[Your Name Here] | Comments Off |

[Your Name Here] | Comments Off |  Sgt. Pepper,

Sgt. Pepper,  The Beatles

The Beatles